Gentle Guide ➺ Ageing

Better with age?

The Clooneyfication of wine is something often referenced, but not always fully understood. Increasingly, the catch-all statement that wines ‘get better with age’ is being challenged. Not untrue perhaps, but not always true – at the very least, we think it’s important to know what the qualities in wine are that you enjoy, and whether those qualities are magnified with some time in the cellar– before you go squirreling away your choice nuts.

These days, a hefty percentage of producers simply aren’t making wine with the assumption that their customer will be laying it aside to await the long-promised ‘optimal drinking window’. Ready to drink styles have gained plenty of popularity, especially in Australia. Younger wines tend to have more primary character; that’s fruity flavours from the grape itself– berries, cherries, apple, melon, depending on the variety. You’re more likely to enjoy an aged wine, if you prefer wines that taste more ‘winey’ and less ‘fruity’, with more of the secondary and tertiary aromatic character that develops with time.

Those brighter, fresher fruit flavours become a bit more subdued with cellaring time, taking on jammy, more caramelised character consistent with dried fruit. Also coming to the fore; aromatic qualities imparted by oak, such as cedar and tobacco, or warm, woody spices like cinnamon, nutmeg and clove. As aromatic compounds in the wine continue to transform, particularly in response to oxidation, we can see development of richer, deeper characteristics, like mushroom, truffle and earthiness. Flavour and aroma becomes more complex, including less obvious character like leather, kerosene or cured meat.

What causes these changes? Many factors of course.

A notable one is the softening of tannins in wine. Tannins are phenolic compounds from the skin, stem and seeds of grapes that add bitterness and astringency to a wine– think of black tea and dark, bitter chocolate, both high in tannin.

A high tannin wine often has a drying, acidic quality that can be unpleasant if not well balanced. The longer a wine sits in bottle, the more that tannin molecules undergo polymerisation; formation of long-chain molecules that are gentler drinking due to larger surface area, eventually reaching a size where they’re likely to settle out of the wine altogether as a sediment. This leaves the wine mellower.

to age or not to age

Another is oxidation. Oxygen is a reactive element that strips electrons from other compounds, transforming them as it does so. This can be a good thing, like when we decant a wine to ‘let it breathe’ – we’re letting some of the aromatic esters in the wine react with air, opening up and transforming. However, too much oxidation over too long a period of time can be detrimental, converting alcohol to vinegar. No bueno.

So, to age, or not to age? No easy answers, only experimentation. Try some aged wines when ordering out, compare them with younger vintages on the list. If you enjoy aged wines, consider buying a case of your favourite style, and sample every few years to identify the changes taking place. You’ll find there’s a sweet spot, beyond which, the wine deteriorates. We can’t all boast impressive, subterranean cellars, but if you do decide to hold onto some bottles for future sampling, aim for a space that’s cool (12-15℃), dark, of consistent temperature, and protected from vibration, ensuring stable conditions for your wine to age well.

cellaring potential: drink young

not sure where to begin?

Choose wines of higher acidity, less than 15% alcohol, made from high-quality grapes. Australian Shiraz and Cabernet Sauvignon are certainly known for their ageing potential, but cool climate Pinot Noir, and sweeter, more acid driven whites like Riesling and Semillon can also yield remarkable transformation when treated to a little time. Brighter fruit and softening acid give way to richness and honeyed complexity not seen in younger iterations.

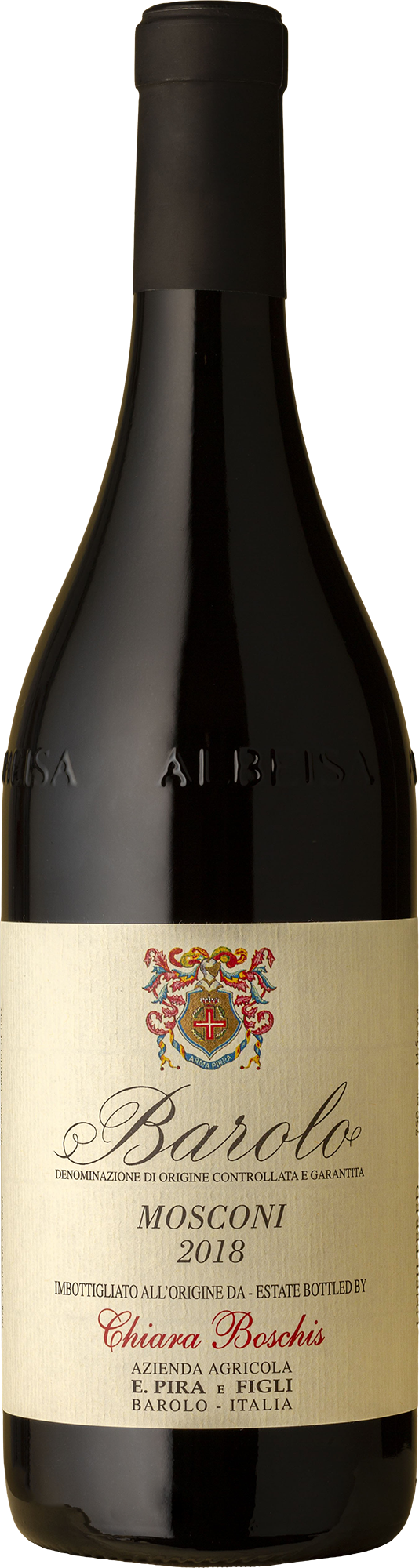

Other classic styles to hoard? You can’t go past the best of Burgundy. While many Burgundian whites will develop nicely within 5-10 years, some of the Pinots can be set aside 30 or more, making them a great option to mark a milestone. Lay one aside when a wee babe is born, then decide whether to share based on how they turn out. The bitterness common to younger Sangioveses, blended or otherwise, will dissipate after 5 or so years ageing, while sweeter-styled Chenin Blanc, such as those from the Anjou region of the Loire Valley or even some of the South African new kids, become something spectacular in 5-10.

cellaring potential: long term

Champagne could be a piece all of its own (actually, we did that), though a good rule of thumb is that the sweet spot for a non-vintage champers will be between 3-5 years, while a vintage cru will enjoy 5-10.

May your future self thank you for your foresight. Or, if you’ve been sitting on something special that might be about to turn the corner, let this be the nudge you need to pull a cork today. Happy sipping, to young and old.